The Midnight of Myth

Addressing the inaccuracy of how superhero stories present our world

In a heterogeneous culture comprising a variety of communities with different traditions, languages, and histories, shared symbols and iconography in the narratives available in public entertainment encourage social cohesion and shared identity. Our narratives act as a universal language, allowing individuals from various cultural backgrounds to communicate and understand each other with reference to common stories and symbols, fostering empathy and breaking down barriers between different groups. With collective ethical principles encapsulated in shared narratives and iconography, public touchstones like superhero sagas help in transmitting cultural values intended to guide a society’s members, in providing an ideological framework through which to understand the world, and in connecting them to a larger community—altogether, endowing audiences with a sense of purpose and security while contributing to a more cohesive and harmonious society.

One of last season’s slices of Radio Free Pizza centered on similar claims, arguing that superhero stories function as modern parables, addressing complex ethical dilemmas and conveying moral values to readers. Of course, that sentence’s last clause—addressing ethical dilemmas and conveying moral values—describes the substance of fiction in general. Perhaps for that reason, recent decades have borne witness to the ascendance in cognitive science and behavioral psychology of related ideas about the importance of storytelling in decision-making. Prof. Nick Chater of the Warwick Business School offers a nice introduction to those ideas with The Mind Is Flat (2019), partially excerpted here.

In that excerpt, Chater argues that the stories we tell ourselves about our motives, beliefs, and values are not just unreliable but entirely fictitious. Instead, we reference the same storytelling mechanisms to interpret the actions of other people and ourselves as when we interpret the actions of fictional characters.

Chater presents three strands of evidence to support this claim:

Linguistic explanations we create about our own behavior are generated by the language centers in the left cerebral cortex. Through experiments with split-brain individuals, he illustrates that the left brain, responsible for language, can confabulate explanations for actions carried out by the right brain, even when it lacks direct knowledge.

Psychological experiments demonstrating that humans often create stories about their motives, thoughts, and emotions. Examples include the influence of adrenaline on perceived attractiveness and the phenomenon of choice blindness, where individuals justify choices they never actually made.

Attempts using artificial intelligence to reveal the real causes of human behavior and to replicate human expertise in computers have failed so far. Meanwhile, experts themselves often struggle to articulate how they arrive at conclusions in fields like medicine, weather forecasting, or chess playing, implying that the process of articulation involves different cognitive regions than those used for decision-making in their field.

Overall, Chater asserts that the human mind is a prolific storyteller, continually generating explanations, speculations, and interpretations, even about its own thoughts and actions. He suggests that introspection—the process of interpreting our own motives and behaviors—is not a direct perception of some inner truth, but rather the human imagination turned upon itself. His central thesis is that the stories we tell ourselves about our lives may be as fictitious as the narratives we create for fictional characters, and (importantly) that we construct stories for ourselves according to the same narrative instincts used to interpret characters’ motives in fiction.

I suppose I must have had the same idea when I improvised the abstraction of the Pizza-Man saga—starring as certain a self-insert as any that has ever existed (so obviously that from now on we’ll just say that “Zaquerí Nioúel” is his secret identity)—to illustrate how superheroes stories stage social concerns, encouraging critical reflection on societal challenges and on how we relate to them.

Framing social concerns as the members of Pizza-Man’s rogues’ gallery helped me to swiftly communicate in a shorthand manner my opposition to what those symbolic stand-ins represent, and why I oppose it. Such symbolic antagonists, and other conventions of superhero stories (like a penchant for the archetypal hero’s journey), account for the broad appeal, helping them transcend ideological and religious boundaries: for that reason they’ve become part of today’s cultural lexicon, providing shared references, through comics, movies, cartoons, and other media, that people can relate to across diverse communities while discovering a collective value system shared between them through the heroes they celebrate.

Because superheroes embody qualities such as courage, resilience, and justice, their stories inspire individuals to aspire to such virtues, fostering a sense of unity around these common ideals that go beyond cultural or religious differences. Since the dramatic conflicts of superhero stories frequently stage contemporary social issues, these narratives provide a platform for discussion about these challenges and for reflection on one’s personal relationship to them.

But if those stories (or the narratives of popular entertainment in general) fail to adequately stage the issues our society confronts, audiences become misinformed about their relationships to those challenges. Moreover, because the settings of our narratives don’t match the world in which we live, our fictional heroes therefore model nothing of how we might confront those challenges in reality. In the end, we find ourselves with an impoverished culture trafficking in unsatisfactory narratives that tell us less about the world in which we live or how we might go about living in it, and—it seems to me—our society consequently lacks real-world champions who can exemplify any virtue in their responses to our present concerns.

That mismatch between the social concerns present in today’s superhero narratives and those that face us in the real world undoubtedly stems in part from the genre’s past use as a tool for state propaganda and for social engineering, limiting those stories’ capacity to address real societal issues. Nonetheless, I previously emphasized the importance of creating narratives that inspire positive change and social awareness, and I still champion the superhero genre as a vehicle for them: despite the aforementioned dangers, nonetheless I maintained the utility and importance of symbolic figures like superheroes and their shared mythologies.

Of course, that shouldn’t obscure our view of historic occasions on which superhero stories did serve the purpose of imperial propaganda. Certainly Nat Yonce’s Collective Action Comics doesn’t lose sight of it: in fact, this wonderful podcast spends its second season covering it, as embodied in Mark Millar’s The Ultimates (2002–’04) and its staging of the Bush Administration’s interventionist foreign policy following 9/11.

That season demonstrates convincingly that The Ultimates exemplifies how cultural commodities can function to manufacture consent for (and stifle opposition against) imperialist U.S. foreign policy. As Yonce puts it in “Vol. 2, #1” (at ~7:36):

Mark Millar’s The Ultimates represents the knife-edge, the capstone of the pyramid of the United States’s attitudes towards control. An unelected, unaccountable handful of powerful individuals are sanctioned by an imperial state hell-bent on expanding its power to subjugate. Using a sleight of hand that reaches far beyond comics, this book performs a task that on the surface contradicts itself: it obscures the violence of empire by celebrating the monsters who commit it.

For Yonce, it seems that Millar’s titular team (featuring Captain America, Iron Man, the Hulk, the Wasp, Giant-Man, Thor, and Nick Fury of S.H.I.E.L.D.) could be taken as symbolic of the ruling class and the accumulation of its economic power under capitalism. As explained in the same episode (at ~9:08–11:52), the economic shifts of the ’80s under Reagan in the U.S. and Thatcher in the UK removed constraints on corporations and undermined unions, allowing both the further concentration of profits in the hands of shareholders and executives, and the further weakening of workers’ rights.

Since the capitalist mode of production encourages employers to pay workers as little as possible, domestic socioeconomic inequality inevitably results—even as profits further balloon with the imperial conquest of foreign markets under globalized neoliberalism—requiring an increasingly militarized law enforcement to preserve the system benefitting the capitalist class.

However, we might also take The Ultimates as symptomatic of the popular ideology that supports the domestic industrial austerity and the imperial foreign policy serving the ruling class. In Yonce’s analysis (at ~28:02–31:47), the availability of such a critique reflects the inadequacy of Millar’s liberal-progressive worldview for addressing the structural imbalances inherent to the capitalist mode of production or the imperialism it encourages. While Millar describes his political stance as “‘traditionally left-of-center and progressive,’” Yonce argues that a left-right political spectrum obscures the true dynamics of power distribution, which ought to be viewed in terms of a vertical (concentrated power) versus horizontal (evenly dispersed power) distribution.

With no meaningful political movement in the U.S. advocating for a horizontal distribution of power, progressive liberals like Millar—despite potentially noble social goals or anti-establishment posturing—have no critique of the economic system propping up the power-structures that produce the very discrimination and inequality which liberals claim to oppose. Or, in the context of superhero stories, they have “no problem representing George W. Bush in unflattering ways” but neglect “the supreme right of the United States to put together an internationally focused, super-powered paramilitary drawn almost exclusively from weapons contractors and die-hard soldiers.”

Such a worldview fails to recognize the importance of understanding imperialism for a comprehensive critique of the U.S.’s self-mandated role as the principal guardian of world security. As Yonce explains (in “Vol. 2, #2”, ~9:36–13:24) imperialism in the current era involves the extraction of wealth from foreign populations for private economic gain:

Although the word empire itself […] may still evoke images of royalty and despots and insignia’d armies riding horses over hills in straight lines, imperialism today is so much more sinister […] as a direct consequence of how obscured and obfuscated it has become. Despite this, a simple axiom helps us part the fog: “Imperialism is capitalism, writ large.” Instead of conquering and enslaving for gold and jewels […] empires today conquer and enslave to install social and economic systems that exploit labor and natural resources […] appropriated to be sold for profit at huge markups […] For instance, Canada today is home to around 75% of all of the world’s mining companies. Canadian mining companies own two of the three largest gold mines in all of Africa […] How is this imperialism? […] the Canadian government has a program called the Canada Fund for Africa, the largest initiative of which is called the Canadian Investment Fund for Africa. The Canadian government has pumped $100 million into CIFA in order to privatize African businesses and services and to accelerate industrial development and to stimulate and expand “mineral prospecting and exploration.” […] Isn't it weird that there now private owners are all in Canada? […] Might the Canadian owners be why the African workers are still very poor? In this new era of international super-profits, imperialism is defined by economic systems that legally enslave large portions of the population.

Imperialism today, Yonce argues, is essentially an extension of capitalism on a global scale, in which the foreign policy of a capitalist republic assists its capitalist class in exploiting foreign labor and natural resources. (I’ll add that the example of Canadian government programs working to privatize African industries for Canadian corporate profit interests me for its potential echoes with the Canadian mining in Panama that Radio Free Pizza covered last year.) Thus the state becomes a tool for class oppression, as Lenin observed.

But figures like Mark Millar, despite expressing anti-establishment sentiments, may still fundamentally operate within a liberal framework that fails to recognize these economic dynamics. While the popular understanding has it that Millar challenges traditional superhero narratives and deconstructs the superhero genre, exploring complex themes and moral ambiguities while deviating from the conventional portrayal of superheroes as purely virtuous figures in favor of darker, more flawed depiction, the absence of any economic critique means that Millar’s provocative reimagining of iconic characters still serves the interests U.S. imperialism.

Certainly Yonce finds that as regrettable as I do. In “Vol. 2, #3”, he reflects (at ~35:12–38:25) on the “deeply uncynical love for superheroes” that numbers among the few affections that he and Millar seem to share:

I love them to my core. The child in me can connect to the comforting simplicity of having the right power for the job. There’s a reassuring joy in the party that’s objectively correct, absolutely wailing on an adversary of unquestionable evil and winning every time […] They fit, however messily, into the slots carved for them by writers and artists, and complete a tableau of conviction and integrity. In a word, they are symbols […] Any team of writers and artists can take over any superhero book and generate content, if you will, regardless of the relationship those characters or those creatives have with an audience at large […] Some writers love superheroes, and some writers merely use them […] Mark Millar loves superheroes […] In my opinion, it’s Mark Millar’s love of superheroes that translates to his trusty utility belt of symbols. Millar understands the power of conveyance and implication that symbols have.

But with his shallow understanding of economics and geopolitics, Millar’s narratives deploy those symbols in ways that reinforce the ideology justifying imperialist extractions abroad and police-state measures at home. As Yonce explains in “Vol. 2, #4” (at ~33:59–38:37), the surplus production of weapons, not used by the armed forces, is either sold to other governments for suppressing resistance or given to local police departments to use against the civilian population. The police and the armed forces are seen as fulfilling the same function—enforcing the capital order’s control over politics and the economy—as in the 1999 protests against the World Trade Organization (WTO) known as the Battle of Seattle, where the police responded brutally to protect the interests of international bankers and industrialists.

But Millar would have us believe that the superhero Thor protested at the Battle of Seattle but accepted in essence Nick Fury’s “‘tempting offer to cut my hair and join the United States Marines’” nonetheless. As Yonce puts it in “Vol. 2, #6” (at ~30:50), “Apparently, all it takes to get Thor—committed revolutionary—to hobnob with the world’s third richest man is to just make some jokes and act friendly. Remember, never once in this book is the word ‘capitalism’ used, so it’s not surprising that Thor doesn’t actually stand for anything meaningful.”

In the same episode, Yonce lays out (at ~54:24–56:56) how—unfortunately for The Ultimates, but luckily for our analysis of modern superhero stories’ shortcomings—Thor functions here as an unintentional symbol for the ineffectuality of progressive liberals:

[Captain America] asks Thor if he thinks the Earth really needs to be purified. Thor basically says yes because the world is being bled dry while we all watch reality television and play PlayStation 2. Tony asks Thor if he thinks joining the Ultimates could provide him with a useful platform for spreading that message. And again, Thor says exactly what he should say[:] “Joining the Ultimates would be condoning every reprehensible action taken by the wretched military-industrial complex who pay your wages, Tony” […] That’s a good answer. But that’s all it is. It’s just words with no action and no deeper consideration behind them […] He mentions not wanting to work for the “ruling class” and I want to touch on that briefly: this is a man who’s apparently made a fortune off self-help books. Self-help books are, by their very nature, individualistic [...] Hence the very existence of a self-help book. Anyone serious about societal change understands fundamentally that this cannot be enacted on an individual level. So when Thor speaks here of a corrupt ruling class, I can’t take him seriously as he, a corporate self-help shill, doesn’t seem to know what the fuck a class is.

The inconsistency that Yonce identifies in Millar’s characterization of Thor—highlighting how the character’s words lack corresponding actions and reflect a shallow understanding of political and economic realities—gives us reason to question not just Thor’s comprehension, but Millar’s and that of those who share their progressive liberal worldview, of how capitalist republics operate. Because of that worldview’s blindspots, Yonce argues in the same episode, movements such as those supporting women’s liberation could be co-opted into promoting individualist consumerism under the deceptive guise of social progress.

Naturally, such mismatches between reality and ideology help the efforts of the U.S. empire to manufacture consent for war, as with the intensive propaganda campaign preceding the 2003 invasion of Iraq and during the publication of The Ultimates. In “Vol. 2, #7”, Yonce explains (at ~31:47–32:51) how mainstream corporate outlets distribute these coordinated propaganda campaigns, conducted throughout the media—including in entertainment media like comic books and their superhero-movie adaptations—to influence audience opinion and that of creators like Millar:

The U.S. had a term for all this that you probably remember: “hearts and minds.” It's through this lens that we have to understand the social and the media side of power, to shape an opinion, to concoct and conjure support where once there was none, to manufacture consent […] The U.S. uses its worldwide media apparatus to condition its citizens to champion its wars and to accept oppression that it perpetrates. It broadcasts messaging and distributes misinformation at home and abroad designed specifically to make it easier to destroy the fabric of societies it views as nothing more than useful. Certainly not immune to this was Mark Millar.

Hinting here at Millar’s susceptibility to the influence of propaganda distributed through imperial media, Yonce suggests that even individuals involved in creative endeavors like comics are not immune to the impact of media conditioning, to which he aims to respond with the critiques found in Collective Action Comics.

But I believe that response has greater import than just demonstrating misunderstandings and correcting misinformation. In fact, I argue, this line of thinking goes some way toward outlining how we can rejuvenate the shared narratives through which a heterogeneous culture finds social cohesion and group identity.

As I see it, the mismatch between the world inhabited by the heroes of our shared narratives and the world in which we live each day has catastrophic results for the society operating within a culture trafficking in mismatched narratives. For this reason, it seems to me, those of us living within the empire (or within that imperial culture’s sphere of influence) have been left with fewer real-world heroes, whom have had enjoyed less opportunity to observe characters acting heroically in a world governed by forces matching their own. On this note, Yonce discusses in “Vol. 2, #8” (at ~26:22–27:52) how using warped justifications for imperial violence according to notions of “good” and “evil” seems to have left those in the empire with nothing to stand for beneath our symbols, and quotes the prominent Iranian cleric Shahab Moradi on the January 2020 assassination of Major General Qassem Soleimani ordered by then-President Trump:

“In your opinion, if anyone around the world wants to take their revenge on the assassination of Soleimani […] who should we consider to take out, in the context of America? Think about it. Are we supposed to take out Spider-Man? And SpongeBob? They don’t have any heroes. We have a country in front of us, with a large population and a large land mass, but it doesn't have any heroes. All of their heroes are cartoon characters. They’re all fictional.”

This objectively sick burn cuts right to the core. When was the last time you heard of anyone in the U.S. government actually accomplishing something good for the people, something pure and unfettered by compromise, or not justified by tortured statistics?

In Moradi and Yonce’s views, the immorality of U.S. foreign policy comes naturally paired with a scarcity of heroic figures in modern American society. This, I argue, proceeds as an inevitable consequence of our cultural narratives’ failure in authentically staging the material realities of our world today and, more significantly, the ideologies that produce them.

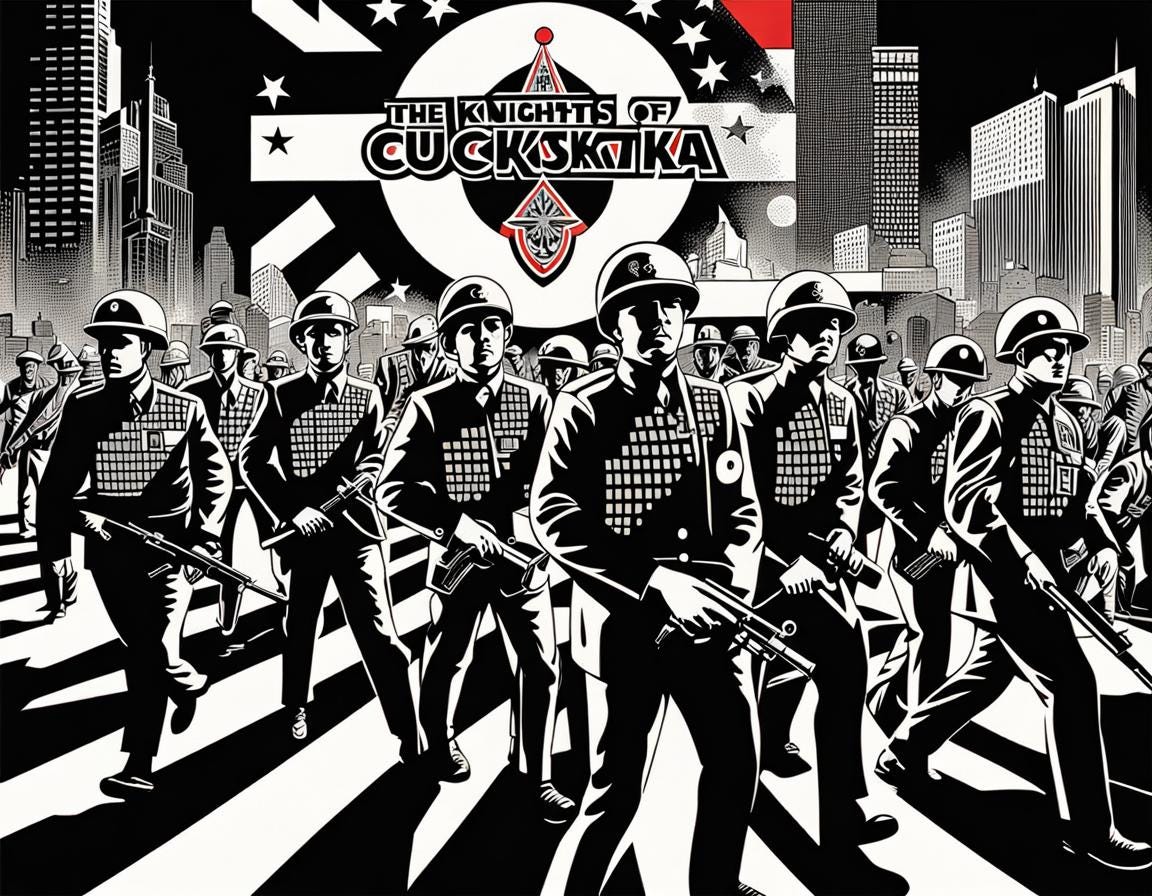

Maybe nowhere is that failure more obvious than in the origins of Captain America. Created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, the character debuted in 1941, after the U.S. had entered the war against Nazi Germany as a symbol of American patriotism and resistance against the fascist powers. His early comic book adventures vividly depicted him punching Adolf Hitler in the face, making a bold statement against the real-world menace of Nazi Germany. Captain America’s role as a superhero and propaganda tool during this period reflected the spirit of the times, providing a fictional champion embodying the fight for freedom and justice during a critical chapter in history.

But unfortunately, Captain America’s origin-story obscures the true relationship between the U.S. and Nazi Germany. Lucky for us though, Collective Action Comics takes pains to clarify it. In “Vol. 2, #12”, Yonce gives an account (at ~13:04–20:22) of how imperial American finance funded the Nazi German war machine. Delving into the historical context of Nazi Germany’s industrial rise and its connection to foreign capital and exploited labor, Yonce specifically highlights the role of an organization familiar to Radio Free Pizza aficionados: the Bank for International Settlements (BIS)—not just “integral to Germany’s looting of countries it conquered” during the war, but in channeling British and U.S. money into German corporations like IG Farben (enduring in part as Bayer following its postwar reorganization) and Volkswagen before the conflict began—in contributing to Germany’s rapid militarization, and connects this funding to the broader theme of international capital’s collaborations with fascist regimes.

Corporations such as Standard Oil of New Jersey, the Chase Bank in Nazi-occupied Paris, Ford Motors, and the International American Telephone Conglomerate all engaged in profitable dealings with the enemy during World War II. In fact, Yonce tells us, “President Franklin Roosevelt himself signed the Trading with the Enemy Act only five days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, specifically so that the U.S. entering the war would not disrupt the flow of international capital.”

Unsurprisingly, that foreign capital which could freely cross battle-lines had taken advantage of the forced labor and industrial austerity that constituted economic policy even in peacetime Nazi Germany. Doing so, Yonce tells us, involved implementing the brutal methods of factory production developed by Charles Bedaux, an American systems designer, in Nazi-controlled areas of Europe. That, of course, showcases the collaboration between American corporations and the fascist regime in exploiting those occupied areas’ workers.

(Today, Yonce reminds us, “the United States has the largest forced labor system in the entire world now, with 25% of all prisoners anywhere,” demonstrating once again how the violence resulting from imperialist foreign investment returns home to harm the domestic population.)

Later on (at ~34:42–36:58), Yonce specifically highlights the Bush family’s historical connections to the connections between imperial finance and fascist regimes. In 1931, the same year in which the BIS was formed to process Germany’s WWI reparations, George Herbert Walker and Prescott Bush (grandfather and father to George H.W. Bush) hosted the Third International Congress of Eugenics in New York City—as good a place as any to rub elbows with Nazis, I suppose. In 1934, Prescott Bush took control of Union Bank’s German operations, profiting from the merger of German steel manufacturers supported by Hitler’s government. With Union Bank linked to United Steel, which the U.S. Treasury Department found in 1945 to have supplied parts for Nazi war munitions (“sometimes up to 50% of the total used by the Nazis”), Prescott Bush had become essentially the Nazis’ U.S. banker.

By pointing out that corporate entities supporting the Nazi war effort like Volkswagen and Bayer still exist and inform policies today, Yonce reveals the continuity and persistence of fascist influence. Not only did the individuals and institutions responsible for financing those companies profiting from forced labor manage to evade consequences, but they went on to secure (for themselves or for their descendants) esteemed positions in contemporary society.

Of course, none of that sounds heroic. But it fits with the Marxist-Leninist framework of imperialism, to which Yonce returns in “Vol. 2, #13” to discuss (at ~1:54:42–1:57:19) how Vladimir Lenin’s “Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism” (1917) enlightens readers about the influence of global capital flows and geopolitics that develops under imperialism. In that influential essay, Lenin argues that in response to a surplus of capital in developed countries, corporations seek increased profits by exporting capital to underdeveloped nations with low wages and inexpensive resources. Capitalism’s inherent drive for profit maximization leads to monopoly capitalism, where a few corporations dominate industries, and a concentration of financial power in fewer banks, which increasingly control the finance capital used in industry. Lenin contends that imperialism, the extreme of capitalism, arises as finance capital takes control of military might, technology, media, and social manipulation. The export of this financial control becomes more crucial than exporting actual goods.

Yonce explains further how, in the post-World War II era, capitalist powers within the United States have leveraged the nation to establish control over the world’s economic affairs—through (if I may add my own gloss) the country’s influence over the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and the petrodollar system, among other useful levers like the World Trade Organization, the World Economic Forum, and others that Radio Free Pizza hasn’t yet had time to cover—marking the pinnacle of imperialism.

Accordingly, it’s worth asking: what can we do about it?

Yonce explores that question in the conclusion of the same episode (at ~2:08:30–2:11:17), and identifies a significant obstacle:

Because the capital class dictates our media and our education systems, anti-communist propaganda is absolutely indelible in our brains. Thus, even sober factual presentation is often met with resistance and rejection […] so many of us sit there and assume that there’s nothing to be done about it, that the villains have won simply because there aren’t any heroes. This isn’t the case. We're all heroes. When those of us who work for a living […] stand up together and refuse our oppression, we’re heroes […] When we feed our neighbors and look after their children […] we’re heroes. We’re heroes in every act of defiance that we do and we can do them daily, but we can also be so much more. There’s a momentum to heroism. There’s a momentum to change. And the last thing the billionaires destroying our future want is for us to sustain that momentum. That momentum comes from deliberate organizing […] It comes from a place of discipline, commitment and responsibility to each other and to tomorrow […] As long as there is momentum, then ultimately, there is hope.

In the face of complex issues often misunderstood, Yonce emphasizes the power of collective action and everyday acts of defiance, recognizing that each person has the potential to be a hero by standing against oppression, rallying against injustice, and engaging in acts that promote positive change. Mass movements for popular liberation from the capitalist mode of production require a sustained momentum that builds more easily when people organize deliberately, commit to shared responsibilities, and challenge the forces that threaten their futures. As long as there is resistance and momentum, Yonce maintains, hope persists in the fight against those who jeopardize happiness, lives, and the planet—and with that idea, Collective Action Comics’ second season comes to a close.

Yonce’s season-long examination of The Ultimates through a Leninist lens underscores not just the pervasive influence of global capital flows on geopolitics, but on the use of entertainment media as propaganda to excuse, justify, and manufacture consent for military adventurism to benefit international finance. Such are some of the potential pitfalls, I argue, that arise when our popular narratives fail to align (or intentionally obscure) real-world issues and their economic contexts.

For that reason, it’s important to analyze the degree of authenticity with which superhero stories represent societal challenges. The genre’s historic function in propaganda demonstrates its usefulness for shaping public perceptions: for example, only through omitting the intricate connections between American finance and Nazi Germany could any writer stage the symbolic representation of the United States as an uncomplicated protagonist with a fundamental opposition to any fascist antagonist.

Whether those real-world complexities are included or omitted has profound implications for how superhero stories impact society. As modern mythological figures, transcend cultural boundaries and provide a common ground for diverse communities. superheroes hold immense potential for fostering social cohesion can only be honestly realized if their stories faithfully stage the world in which we live: the material conditions that appear in it, the mode of production responsible for them, and the imperial conquests that this encourages. Without that faithful staging, the narratives of popular entertainment fail to authentically mirror the complex issues of our society, raising concerns about the potential not just for misinformation, but for preventing genuine role models from developing in the real world.

After all, the aforementioned Chater’s insights into human storytelling reveal the profound impact of narratives not only on our understanding of the external world but also on the construction of our internal realities. It stands to reason, therefore, that narratives featuring protagonists who embody virtues like courage and a commitment to justice will prove more inspiring—will, indeed, give audiences a more intimate understanding of how a person behaves when heroic motives guide them—the more faithfully they represent that external world and the forces acting on it. That inspiration alone, the impulse to aspire to higher ideals, fosters a sense of unity beyond ideological and religious differences. But for that shared impulse to unite us, the source of its inspiration must recognize what truly divides us.

In the end, the disconnect between the fictional settings of our narratives and the real-world challenges we face represents a significant obstacle to addressing our collective concerns. We can attribute this misalignment to the genre’s historical use as a tool for state propaganda and social engineering, which (certainly in the case of The Ultimates, anyway) limited its capacity to authentically address societal issues.

But despite the dangers and historical baggage, writers and artists today would do well to recognize the superhero genre as a vehicle for narratives that inspire positive change and social awareness. That, of course, comes with the responsibility of exploring concepts of vast dimensions—like the mode of production according to which our society has organized its industries; or the imperial extractions, military adventurism, and war-profiteering following from it; or the political ideology guiding creators of the media content commercially available within that society; or what that content’s narratives contribute to the contemporary culture of those audiences who consume it. But only by meeting this responsibility can creators develop narratives that not only entertain but also enrich our understanding of the world, providing a cultural lexicon that speaks to the diverse tapestry of our global society.

Through thoughtful storytelling and a commitment to authentic representation, the superhero genre can continue to evolve as a dynamic force for fostering a more cohesive, harmonious, and purpose-driven society with entertainment capable of inspiring real-world heroes to address our world’s pressing issues. Symbols, narratives, and iconography have an immense capacity for sustaining a shared culture, helping individuals to discover collective values and find common ground in a heterogeneous cultural landscape. But for superhero stories to fulfill that purpose, they must do more to illuminate that landscape: to chart it more accurately, and to better indicate the forces shaping it.